The Motion of Music

Originally published in the Folk Harp Journal Spring 2011 No. 150

Written notation is a wonderful thing. With it we can save music, set it in stone

so to speak. Someone alive today can realize tunes unheard for a hundred years if only they know the meaning of the marks on the page. This is, of course, a limitation: one must be able to read what is written.

There is another limitation in written music, of a completely different sort. It is the influence of reading music with the eyes; seeing sound represented in discreet symbols that each have their own individual meaning. Written notation influences our perception of melody. Like words in a poem, notes on a staff cut a complete thought or phrase into pieces. As note follows note we focus our attention on individual elements and lose sight of the whole. We see the writing, and forget we are in a forest of sound.

Pitches and duration are not all that must be represented for music to be complete. For those who play on very resonant harps there is also damping to be considered: the control of that resonance. This is particularly true for the wire–strung harp. How do we write ringing and damping? Using the modern notation assumption that everything has its own symbol, we add another mark to weigh down the page: a small x

perhaps, to indicate the note to damp. And then we had better put in the finger number that will do that damping, perhaps enclosed in parenthesis, as has become the standard for wire–strung harp music.

We begin to see the collection of movements not as a note and another note and a damp, but rather as a single gesture

This approach works, and obviously has its value. We can communicate both music and technique on paper, but it can lead to a perception that music consists of, do this, then that.

We get lost following directions and forget about making music. Phrasing, shaping and interpreting the melody become something to turn our attention to after we have learned the notes and the fingering.

Recognizing this potential for fragmentation is an important step in moving beyond the printed page. The concept is similar to reciting a written poem. If we focus on each individual word, we stand to miss the essential sound of the poem, the rhyme of vowels and the rhythm of consonants. Set in stone

becomes three distinct words, rather than a single breath of sound that escapes our lips to communicate a single thought. Can’t see the forest for the trees

loses its sense if we parse each word’s distinct meaning.

The concept of musical figures is similar to these figures of speech. Rather than look at a series of three movements at the harp as distinct items to be performed in sequence, we can view those movements as a single expression, a block of sound–creation. We begin to see the collection of movements not as a note and another note and a damp, but rather as a single gesture, like a multi–syllable phrase in a poem without regard for whether it is represented in print as three single–syllable words or one word of three syllables.

Once this perspective is learned, music written using modern notation takes on a different look. We search for the structure the notes realize, looking for patterns and gestures. Musicians who read music notation may find that learning a tune aurally from another musician becomes easier with this new perspective. They can be free from instructional–based aural learning: play this note, now this one, and finally play a note a skip down

and instead move to: perform this gesture starting on D.

Many musicians already take this approach for understanding harmony. We think: play a chord

rather than: play this string, then skip one and play the next one and then skip the next string and play the one above that.

Today we are going to apply this concept to melody, specifically to two basic figures that incorporate both striking and damping. If you are a regular reader of this column, you may remember the written description of these two figures in the Folk Harp Journal’s Summer 2010 issue, in support of an arrangement of Ossianic Air. That description included a representation of those two figures using standard notation.

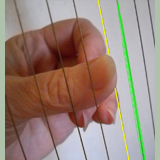

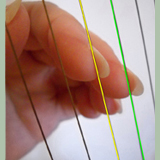

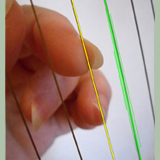

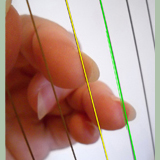

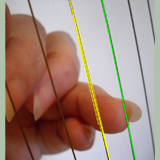

Here now are those same two figures presented photographically. This will take more space on the page than a step–by–step description, but hopefully it will help us appreciate that these movements are one gesture.

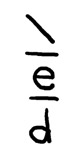

These two figures are found in the Robert ap Huw manuscript of the early 17th century. That manuscript is written in harp tablature, a written system of music that indicates the figures with a single stroke of the pen, giving only the name of the two strings the figure is to be performed on. This notation is given below for each figure.

The Thumb Choke

taked y fawd

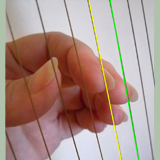

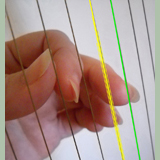

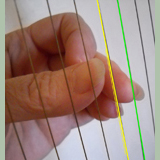

Step-by-step Captions for the Thumb Choke:

- Place the index and middle fingers (fingers #2 and #3) on two strings.

- With the index finger (finger #2) strike the higher of the two strings, which is the yellow string in the illustration.

- As the index finger clears the string, begin to bring the thumb towards that (yellow) string).

- As the thumb touches the higher string, strike the lower (green) string with the middle finger, where it has been anchored and waiting.

- Leave the lower string ringing, the upper string has been damped by the thumb.

The Short Plait

y plethiad byr

Step-by-step Captions for the Short Plait:

- Place the index and middle fingers (fingers #2 and #3) on two strings.

- With the middle finger (finger #3) strike the lower of the two strings, which is the green string in the illustration.

- As the middle finger clears the string, begin to bring the ring finger (finger 4) towards that (green) string).

- As the ring touches the lower string, strike the higher (yellow) string with the index finger, where it has been anchored and waiting.

- Leave the higher string ringing, the lower string has been damped by the ring finger (finger #4).

Editorial changes were made to this article to suit a new layout as an internet website rather than a journal article. Originally published in the The Folk Harp Journal ![]() Spring 2015 No. 166

Spring 2015 No. 166